What happens when your duty to the client conflicts with your duty to the court?

What happens when your duty to the client conflicts with your duty to the court?

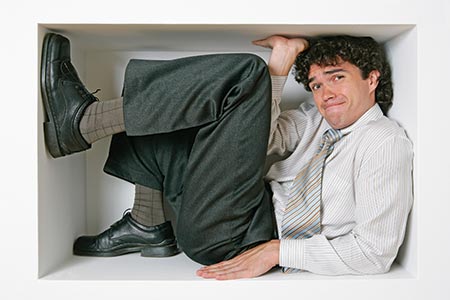

“There are many ways you may find yourself knee deep in mud without realizing it.”

“That’s who I would call if I were you.” I had stumped the Law Society’s practice management hotline. The people you were supposed to call when you didn’t know what to do - they didn’t know what to do. Now I was being referred on to three very senior defence lawyers to try to sort this situation out. What the hell had I gotten myself into?

Generally, giving the police a false name, or otherwise misleading them as to your identity, is a crime. Sometimes you don’t have to identify yourself if a police officer asks you to, but, for example, when you’re driving a car, you must identify yourself correctly if you’re stopped by the police. That part is easy to understand.

But what if the police don’t realize that you’ve misled them, intentionally or unintentionally? Is it incumbent on you to go back to the police and tell them they missed something? But more importantly, for the purposes of this article at least, what is your lawyer supposed to do about it?

This is the situation I found myself in. I felt trapped between my duty to never intentionally mislead the court, my client’s right to silence, solicitor-client privilege, and the overriding systemic necessity that placed the burden of proving my client’s guilt squarely on the shoulders of the Crown.

An individual, let’s call him “Ted,” retained me to represent him. It quickly became clear, however, that he had been charged as “Fred.” The driver’s license he had presented to the police when he was stopped and arrested was in the name of Fred, not Ted. Everything else on the license was correct and accurate and valid. Aside from naming him “Fred,” it was Ted’s license.

Somehow, the police completely missed this. The license passed all the usual checks. Ted told me that he knew the name on the license was wrong, but didn’t tell the police because he didn’t want to get into more trouble. He asked me what he should do.

I didn’t know what to do. I told him I would have to look into it and get back to him.

Ted’s first appearance came up very quickly, before I had had a chance to properly resolve the issue. As had been agreed as part of the retainer, I attended court in Ted’s place.

But how was I to deal with the name issue? What Ted had told me was a privileged communication. I would need a waiver of privilege from Ted in order to reveal the content of that communication to anyone, and I did not have such a waiver. Furthermore, I did not want to ask Ted for a waiver due to the uncertainty over the validity and scope of a “limited” waiver of privilege that currently exists in our law. For example, in Ziolkoski v Unger, the Alberta Court of Appeal determined that a court can review the scope of a limited waiver of privilege and can, in certain circumstances, extend that waiver against the will of the privilege holder. I did not want to open that can of worms.

I was also concerned that I would be giving up a possible defence for my client. The information named Fred as the accused, not Ted. It is incumbent on the Crown and the police to bring the matter to court and to prove the case. It is not my place as defence counsel, nor my client’s place as the accused, to fix their mistakes or help them prosecute the case. To paraphrase Justices LeBel and Fish in R. v. Sinclair, “an accused person does not have an obligation to participate in the prosecution against them.” As an accused person’s lawyer, I definitely did not believe that I should be selling my client out to the authorities. This would be a breach of my duty of loyalty to my client.

On the other hand, I had been told by my client that his name was not Fred, but that he had been the person arrested. If the case went to trial, how could I tell the court that my client was not the accused? I definitely could not do that. That would require me to assert something that I knew was factually incorrect – in other words, lie. What if I said nothing? Technically speaking, did my client even have to show up to court? He was Ted, not Fred. Had Ted even been charged?

I still didn’t know what to do. But given the stakes, I was absolutely sure that I could do nothing without being certain about what I was doing. This was not a time to shoot from the hip and I was nowhere close to being experienced enough to even think of trying to. So I said nothing. I informed the court that I was there as counsel on behalf of the accused, received disclosure from the Crown, remanded the matter, and left the courthouse.

I needed help. I sought advice from other defence lawyers I knew and respected. They had no idea what to do either, but they agreed that I was in an untenable situation. To proceed with the status quo would result in either a breach of my duties to my client, or a breach of my duties to the court. I didn’t need to be told that to breach any of my professional duties was absolutely unacceptable.

My colleagues told me to call the Law Society. Now I was starting to get worried. I was still in diapers, as far as practising law goes, and I had gotten myself into a situation that required calling the Law Society for help.

After a few days of lengthy calls back and forth with the Law Society’s confidential practice management helpline, they admitted defeat. They agreed that leaving the situation as it was would result in a breach of either my duties to my client or my duties to the court, but they did not know what to do. Since I could not breach any of my professional duties, they told me to stop acting for my client until the situation was resolved.

The Law Society lawyer referred me to three very senior defence counsel for help. “That’s who I would call if I were you,” I was told ominously. I knew all of the names on the list by reputation and knew that, given who they were and that I was being told to seek their help by the Law Society, I must have gotten myself into a very dire situation. I went from worry to panic.

I contacted one of the recommended lawyers and explained the situation. He was very willing and ready to help me. When he got back to me the next day, my panic turned into full blown crisis mode:

“Anthony, you’re in a pretty serious situation here. You’ve already misled the court and you’re in danger of becoming a party to a criminal offence. You need to deal with this now, today, before you find yourself having to spend money defending a disciplinary proceeding and maybe even a criminal proceeding.”

When I heard these words, my heart sank. My stomach sank even further. I felt dizzy. I’m pretty sure the walls started moving. My career had just started and now it was about to end.

“I’m going to throw up. I’ll be at your office later.”

As he explained to me, the situation I had landed myself in was not too dissimilar from a case out of the Alberta Court of Appeal called R. v. Doz.

In Doz, an individual named Woitt was arrested for impaired driving. He did not have identification on him and knew he had an outstanding speeding ticket, so he gave the police the name of a friend of his named Hutchinson. He was charged and released from custody as Hutchinson.

Woitt attended at the law offices of Doz and Crane and met Mr. Doz, the appellant, a lawyer with 22 years at the bar. He told Doz what he had done. Doz told Woitt to bring Hutchinson to see him. The next day, Woitt brought Hutchinson to see Doz.

A trial date for the impaired driving charge was set. On the day of trial, Woitt drove Hutchinson to the courthouse to meet Doz while Woitt went to a nearby hotel and stayed in a room there.

The defence advanced by Doz at the trial was that while Hutchinson was the accused, he was not the person who had been charged. The officer was unable to identify Hutchinson as the person he had arrested. Doz then called Hutchinson to testify and Hutchinson denied ever being arrested or ever attending at the RCMP station where Woitt had been held after arrest. When the Crown asked Hutchinson how he had come to know of the proceedings if he had never been arrested, he lied and said that his sister had discovered them and informed him.

Hutchinson was acquitted of impaired driving. When he later telephoned his mother and told her what he had done, she told him that he had committed perjury. Hutchinson eventually went to the police. Doz was charged with obstruction of justice, being a party to the personation of Hutchinson by Woitt, and being a party to the perjury of Hutchinson. He was convicted of all three counts.

The Court of Appeal stayed the charge of personation upon application of the Kienapple principle, as the elements of personation were subsumed into the charge of obstruction of justice. But in argument, the Crown had submitted that the personation by Woitt was a continuing offence that did not end upon his release from custody and that Doz became a party to it later by undertaking this defence. Since the charge was disposed of by Kienapple, the Court of Appeal left the question open.

I had been worried about selling out my client and giving up a possible defence. But according to the Crown’s interpretation of party liability in the circumstances of the Doz case, instead of pursuing a defence, I would have become a party to my client’s continuing criminal offence of obstructing justice.

To fix the situation, I was told that I had to advise my client to present himself to the police station where he had been originally charged and report to the police that he had been charged under the wrong name. I was to advise him that he would likely face new charges as a result, at the least he would be charged with obstruction of justice. Further, I had to tell him that if he did not agree to this course of action and sign written instructions reflecting our discussions, my advice and his choice to follow that advice, I would have to remove myself as his counsel and he would have to find a new lawyer. He agreed to take my recommended course of action and was charged with new offences.

In the practice of criminal law, we stand with those accused of having acted outside the realm of permissible conduct and against the power of the “system”, and in defending their individual rights, we protect the rights of all. But the scenarios are not always extreme: you will likely never have a client bring the murder weapon to your office or tell you where he hid the tapes. There are many ways you may find yourself knee deep in mud without realizing it or suspecting you were headed in that direction. Trust your gut. Trust your colleagues. Ask for advice. Call the Law Society. I imagine that this advice applies to senior counsel and counsel in all practice areas, but for junior criminal counsel, it should be a way of life.

At the next appearance of Ted’s matter, now proceeding with the new charges and under the name of Ted rather than Fred, the Crown provided me with new disclosure. I had to sign an undertaking in order to receive it. The undertaking was styled Regina v. Fred. Still reeling and paranoid from my brush with the wrong side of both the criminal law and the rules of professional conduct, I told the Crown that I could not sign the undertaking as it had the wrong name on it.

“Oh, for God’s sake,” she said in frustration. She took the undertaking from me, crossed out “Fred” with her pen and wrote in “Ted.”

“Better?” she asked, with obvious annoyance. I signed it.

About the Author

Anthony Marchetti, Barrister & Solicitor, Toronto, Ontario