Feedback was always a tricky skill to master, and it’s even trickier now. There are two related reasons: first, the psychological impact of the pandemic and second, the challenge of providing feedback in a virtual world.

THE PSYCHOLOGY

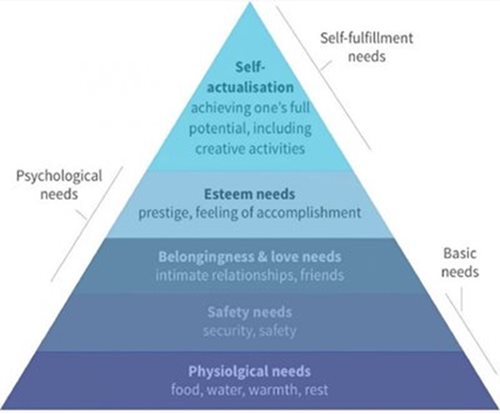

Let’s go back to Psychology 101 and look at Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, shown below. Would you place feedback near the top of the hierarchy? Most would.

In fact, psychologists tell us that feedback sits near the bottom of the hierarchy, somewhere around “safety” or “belonging”. Our brains see feedback as a primal threat, and we go into self-preservation mode when it’s offered to us. Daniel Goleman, author of Emotional Intelligence, explains: “Threats to our standing in the eyes of others are remarkably potent biologically, almost as those to our very survival.”

Today, many people are feeling physically unsafe and thus experiencing a heightened threat response. When feedback is presented against that psychological backdrop, it’s not surprising that recipients quickly shift into survival mode and become defensive. Giving feedback has gotten trickier, so bear in mind a few tips to ensure that your feedback has a good chance of being heard and acted upon.

VIRTUAL FEEDBACK

The most important thing about feedback is remembering to give it, and that’s happening less often in the virtual world. Associates report receiving less feedback since working from home. Those impromptu chats in the corridor have disappeared. Out of sight appears to be out of mind. This is problematic as the absence of regular feedback often leads associates to be unduly concerned about work quality and job security. This in turn leads to a drop in engagement and productivity. Giving feedback requires more deliberate thought than in the past.

Consider the three methods of delivering virtual feedback: email, telephone and video. In a recent blog post, lawyer/psychologist Dr. Larry Richard noted why video is best:

Video is the most emotionally connected medium, and in a time of crisis, you need to foster connection. If video is impractical, do your updates and check-ins via telephone conference call. Only as a last resort use email—it’s less personal, less connected, and invites one-way communication and less give-and-take.

There are exceptions, of course. For example, there’s no sense in using video when giving feedback on a lengthy document if you’ve both got your eyes on the document. The telephone might be the better way to go in that scenario.

When using video, show that you’re 100% invested in the conversation. Turn off notifications and minimize other disruptions to the extent possible. Flip your cell phone over and keep your eyes on the person you’re speaking to.

In a small survey, most associates reported receiving feedback predominately via email. A number noted that feedback delivered this way often lacked detail and sometimes created confusion. Some disliked it because it robbed them of the opportunity to discuss questions related to the feedback. All reported receiving less feedback since working from home.

Because you may not know what your colleague is coping with on the home front, a good practice is to ask what time would be best to connect. If you call when the associate is trying to settle children down for a nap, the associate will be distracted, and the chances of your feedback being fully absorbed will be reduced.

Given what we know about the potential for feedback to heighten the threat response, consider gauging the recipient’s frame of mind and potential receptivity to feedback before launching into it. You can do so by starting the conversation with, “How are you doing today?”. If your colleague is facing a particularly challenging day, you might want to save your feedback for a more opportune time, unless, of course, the issue is time sensitive. It’s critical to show empathy during challenging times. Employee productivity rises when working with people who care about each other. Stephen Covey, author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, notes that when you show empathy defensive energy goes down and is replaced by positive energy.

Once you’ve decided that now’s the time to deliver feedback, it’s useful to start the conversation with a question, for example, “Can I give you some advice?”. Everyone says “yes” to that question. Saying “yes” imparts a feeling of control and releases a dab of dopamine, one of the feel-good drugs in the brain. You’re priming your colleague to be receptive to your feedback. Also, it’s best to avoid the word “feedback”. It sounds evaluative, and we all get stressed at report card time. Unless you’re delivering a performance review, choose another word such as “recommendation”, “suggestion” or “advice”.

Last, make sure it’s a two-way conversation. Feedback is much easier to give and receive if it’s delivered in a conversational rather than top-down manner. After you’ve given your advice, invite your colleague’s input: “What do you think?”; “Does that make sense?”; “Do you think that’s something that you’d be able to do next time?”. You may learn of obstacles that make your suggestion impractical. Further, the associate is more likely to adopt a suggestion if they commit to doing so.

About the author

Deborah Glatter is a legal management and training consultant, an adjunct instructor at Queen’s Faculty of Law and the OBA CLE Liaison.

Deborah Glatter is a legal management and training consultant, an adjunct instructor at Queen’s Faculty of Law and the OBA CLE Liaison.

Copyright © 2021 Deborah Glatter. All rights reserved.

This article previously appeared on the OBA Law Practice Management Section’s articles page.